Genetic Algorithms

Genetic Algorithms are an optimisation technique inspired by natural selection.

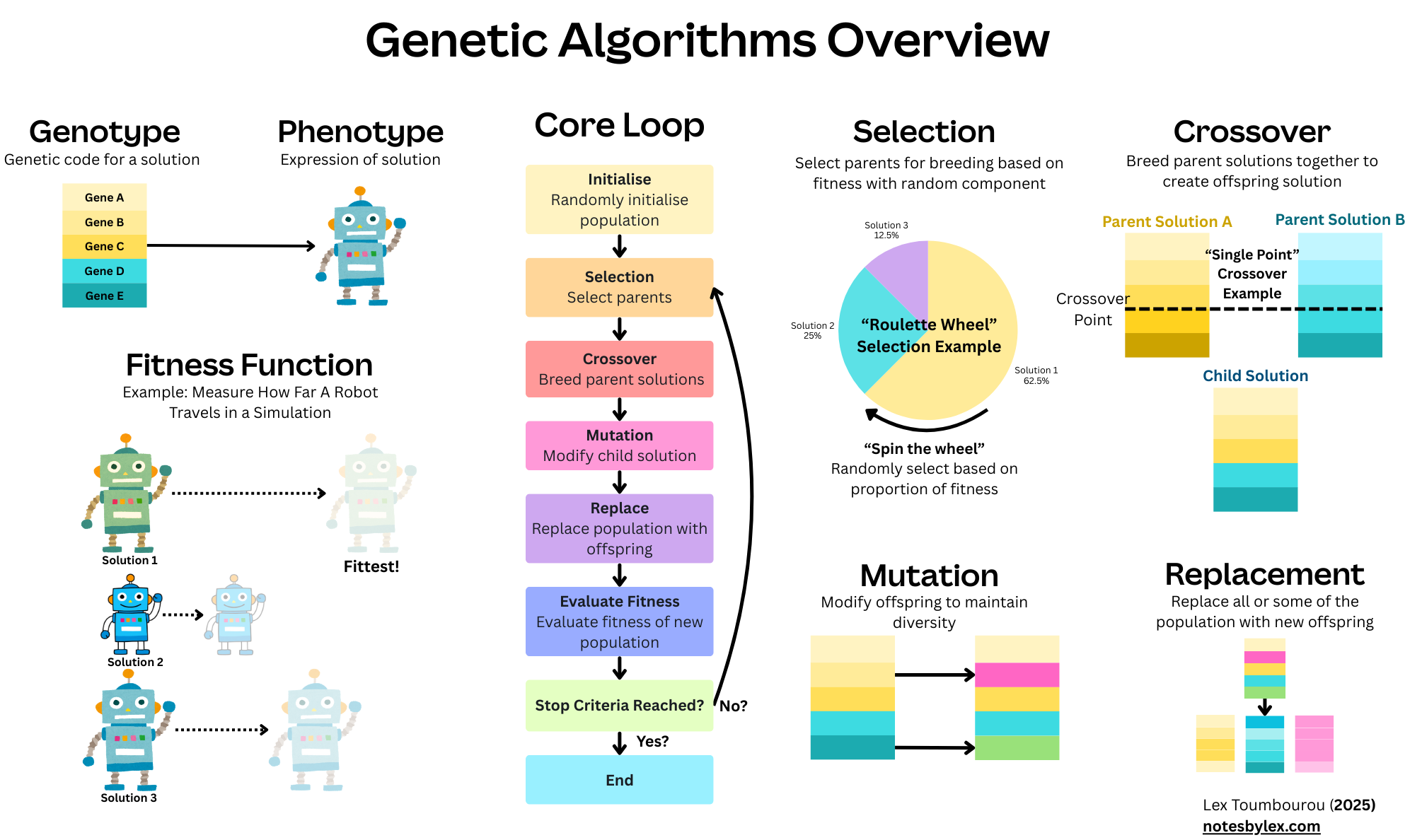

The high-level idea is that we start from a population of possible solutions to a problem, where, importantly, we have a way to evaluate how good each solution is - called a fitness function. Then we perform a loop that involves selecting from the fittest solutions (with randomness), breeding these solutions together, creating mutations, and replacing the population with the new solutions.

The solutions need to be represented in a way that allows us to breed and mutate solutions. Typically, this is an array, where each element represents some parameter of a solution. For example, for testing robot designs, we might have elements that correspond to how many joints they have, and another that describes joint length, and so on. This representation is called a Genotype, a term borrowed from biology, where all living organisms have a genetic code that stores their information, encoded in DNA. The expression of the genotype, for example, the robot that is constructed as a result of the information in the array, is called a Phenotype. In this example, we might utilise a fitness function that tests the robot's ability to complete a task, or to simply move without falling.

The algorithm looks like this:

- Initialisation: Create a random population of candidate solutions genotypes.

- Fitness: Evaluate the fitness of each individual in the population.

- Selection: Select "parents" based on their fitness.

- Crossover: also known as "Breeding", where parents create a new "offspring" by combining the genotype in some way.

- Mutation: the offspring is mutated in different ways using algorithms that involve randomness.

- Replacement: replace some or all of the population with the new offspring.

- Repeat 2-6 until the termination condition is met.

One of the most famous examples comes from Evolving Virtual Creatures by Karl Sims, where he evolved virtual creatures in a simulated 3D environment. In his groundbreaking work, Sims used genetic algorithms to simultaneously evolve both the morphology (body structure) and neural networks (brain/control systems) of virtual creatures.

It has also recently been used within AlphaEvolve, where DeepMind utilised it to explore the solution space for several mathematical and scientific problems. For solutions encoded as software, they utilised LLMs for the code generation and modification tasks, including combining and modifying solutions.

Fitness Function

A fitness function evaluates the population in some way. In the Virtual Creatures example, the fitness is based on how far they travel under different conditions. In AlphaEvolve, the fitness is a test specific to the problem it is trying to solve, designed to find an optimal solution.

Selection

Selection algorithms determine which individuals will become parents for the next generation, giving fitter individuals a higher chance of reproduction while maintaining some diversity. There are a series of common selection algorithms typically used.

Roulette Wheel

When selections are based on the proportion of fitness across the population, think about a roulette wheel as a pie chart, where each pie is proportional to its fitness as a whole. The more fit take up more space, so they're more likely to be selected, but there's also some entropy to ensure the solution space is explored.

- Calculate the fitness of all individuals

- Generate a random number between 0 and the whole fitness.

- Select the individual whose cumulative fitness exceeds that of others.

Tournament Selection

A simpler approach, where we select some individuals at random from the population and choose one of the highest-fitness individuals from each sample.

Rank Selection

Individuals are ranked by fitness, and the selection probability is based on rank rather than raw fitness values. This approach is particularly helpful when fitness values exhibit large variations or when dealing with negative fitness values.

Crossover

Crossover, also known as breeding, is where we combine the genetic material of the two selected parents to create a new offspring. The goal is to create new solutions that potentially inherit the best features from both parents while exploring new areas of the solution space. Different crossover methods are suited to different types of problems and solution representations.

One-Point Crossover

A single crossover point is chosen randomly. Everything before this point comes from Parent 1, and everything after comes from Parent 2.

For example:

- Parent 1:

- Parent 2:

- Child:

Two-Point Crossover

Two (or N) crossover points are selected, and the genetic material between these points is swapped between parents.

Uniform Crossover

For each gene position, randomly choose which parent to inherit from (typically with 50% probability for each parent). This approach provides more mixing than point-based methods.

Order Crossover (OX)

Specifically designed for permutation problems like the Travelling Salesman Problem, where each gene must appear exactly once. In this example, we can switch around nodes (if it generates a valid graph).

Mutation

In the mutation step, we modify the child solution slightly, allowing us to maintain genetic diversity and continue exploring the solution space. There are many mutation algorithms.

Bit-flip

For binary representations, each bit has a small probability (typically 1-5%) of being flipped from 0 to 1 or vice versa.

Gaussian

For real-valued genes, add a random value drawn from a Gaussian (normal) distribution with mean zero and a small standard deviation.

Formula:

Swap Mutation

For permutation problems, randomly select two positions and swap their values.

Insertion Mutation

Remove a gene from one position and insert it at another random position.

Advantages and Limitations

There are several advantages to genetic algorithms over other AI approaches, such as supervised learning. Firstly, no training data is required. If we can construct a fitness function and encode the problem effectively, then we can run a Genetic Algorithm search over the solution space. It can also handle discrete, continuous and mixed variable types. Since each solution is evaluated independently, it is highly parallelisable, allowing cores to be allocated to evaluate one or a subset of the solutions, so it is good when the search space is huge. It is also robust to noisy/weird objectives and can typically escape local optima.

On the other hand, there's no guarantee of finding a global optimum; typically, many parameters need to be tuned, which can be computationally expensive and can easily lead to premature convergence.

Schema Theorem

For the theoretical foundation of Genetic Algorithms see Schema Theorem.