Cross Products

These are notes from Cross products | Chapter 10, Essence of linear algebra) by 3Blue1Brown from the Essence of linear algebra series.

Like the Dot Product introduction, this lesson will show the standard intro to Cross Products, then provide a deeper understanding.

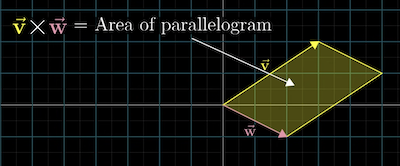

If you have two vectors in 2-dimensional space, think about the parallelogram they create when you copy each vector and move them to the tip of the other vector.

The area of that parallelogram is part of the cross product. Although, when is on the right, then is positive, and on the left, then the area is negative.

That means that the cross-product order matters. If you switched the order, the cross product would become the negative of what it was before.

The way to remember is, if you cross and in order, the result will be positive. If not, it will be negative. For any vector first in the cross product, if it's on the right of the other vector, the result will be positive on the left, negative.

You can compute the area using the Matrix Determinate of the matrix created by putting the coordinates of as the first column and as the second column. That's because a Matrix Transformation equivalent of moving the Basis Vectors to and is this matrix!

If the vectors are perpendicular, the area will be greater than if the vectors are closer together.

If you scale one vector by 3, the determinate is also scaled by 3.

But this operation isn't technically the cross-product. The cross-product operation only exists in 3d space. The actual cross-product combines two different 3d vectors to create a new 3d vector.

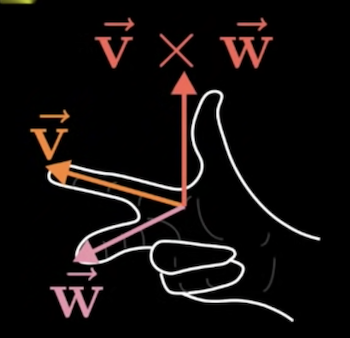

The new 3d vector's length will be the area of the parallelogram defined by the 2d vectors. The direction of the new vector will be perpendicular to the parallelogram.

Using the "right-hand rule," we can determine which direction the new vector will be facing.

Point your index finger in the direction of and middle finger in the direction of . When you stick out your thumb, that's the direction of the cross product.

For general computations, there is a formula you can memorise:

But it's easier to remember an operation that involves a 3d determinant. Create a 3d matrix where the 2nd and 3rd column are and :

Then, the first column should contain the basis vectors , and (even though it is very weird to have basis vectors as entries of a matrix).

You then compute the determinate of a 3d matrix, as if the first column was numbers.

The multiplication on the right returns a number for each part of the expression. Then you scale up the basis vector by that number and take the combination of all scaled basis vectors.